The Adventures of Will Jones by Greg Barron

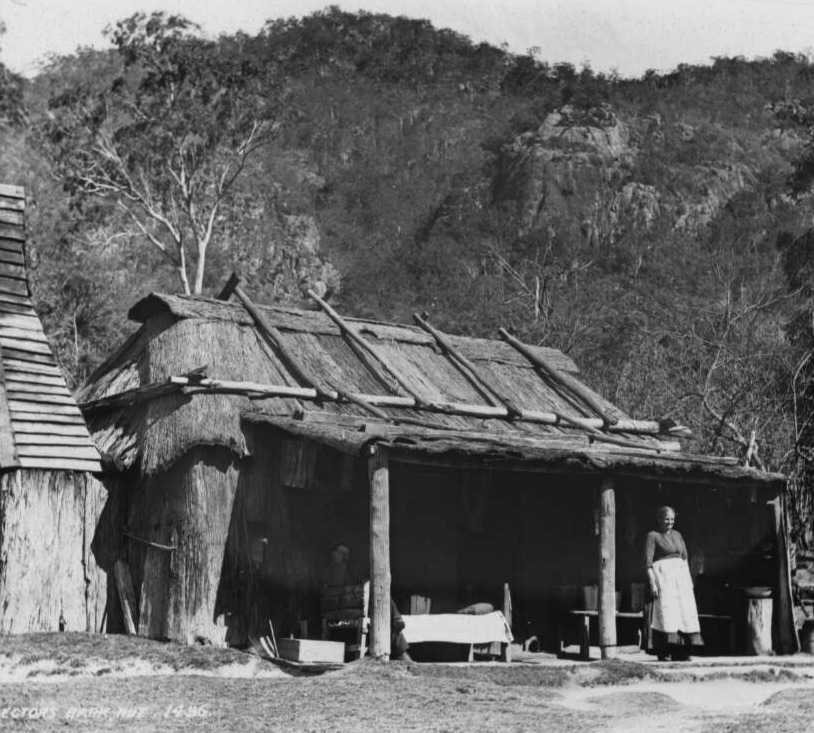

Will Jones was born in a hut hewn of grey gum poles and clad with bark, surrounded by the hills and scrub of the western side of the Great Dividing Range – a sixty-acre selection of sandy flats and rocky gullies, where dingoes wailed their ghostly calls, platypus swam the creeks and crows cawed from the branches of dead trees. The ground here, Will’s father used to say, was three parts stone and one part the bones of humans, black and white, who had broken their hearts on the place previously.

The nearest town was a settlement called Grubben Creek, which boasted a Wesleyan church, a hall, a school and a few houses. There was also a store, the proprietor of which was often at odds with local puritans, for allowing thirsty travellers and working men to drink rum or whisky discreetly in the bough shed out the back.

Will’s birth took place at home, with an inexperienced but enthusiastic neighbour called Hattie Creagh in attendance. She assisted Amelia by reading passages from the birthing chapter of a leather bound copy of The Home Doctor and holding her hand when the contractions came. Luckily, Will arrived without much fuss. At just seven pounds, he was on the scrawny side, but he took to the breast straight off and soon gained weight. He proved to be an affable little chap, who slept all night within a matter of weeks, and smiled and made pleased noises when left alone to play.

The 1860s were boom years for some, and a succession of gold finds were announced like a trail of dominos. Yet, with a civil war raging in America, many goods were unobtainable. Poor selectors struggled with the meanness of the land grant system and the general unproductiveness of their acreage.

Breakfast was regularly interrupted by Will’s father, Christian Jones, whiskered and formidable, slamming the newspaper down on the table. ‘Be hung if there’s a boom. I can’t see no boom ‘round ‘ere.’ He’d been born and bred in the Black Country around Birmingham, England and his accent had not faded one bit.

‘Well there might be,’ said his wife, the much more patient Amelia. ‘If the roos didn’t eat the corn, and the creek didn’t stop running.’

‘You may well say so,’ thundered Christian. ‘But the roos do eat the damned corn, and the creek does stop running. Where’s your damned boom now?’

‘Please don’t swear, dear Christian,’ she would say, then lift young Will to her chest as if to protect the little mite from his father’s language. ‘And would you go into town to see if Mr Strong will allow us another bag of flour until the corn cheque comes?’

The selection provided much of what the family needed, but only through hard work and care. Christian had a repressed urge to join the prospectors who passed by on their way to the latest rush on the Lachlan River near Forbes – colonial lads with elbows and arses worn out of their trousers, the British with their carts bristling with shovel handles and pickaxes, and the Chinese with their pigtails, loads balanced on long poles. Christian would lean on a gate post, smoking his pipe and watching.

‘Yampy fools!’ he would growl. ‘Be lucky to find ‘noof gold to fill a tooth, most of them.’

This cynicism did not stop Christian from taking a rusty gold pan down to the creek, every time he had a spare hour, panning gravel at likely bends in the stream. Over the years he found enough gold dust to look pretty in a jar, two sapphires and some agates. Still, he held that to be an encouraging start, and never let go of the idea.

As an infant, Will was part of farm life, strapped to his mother’s upper body as she picked or husked corn, drove the cart to fetch water, chopped kindling or turned the spinning wheel, making yarn to knit warm clothes for winter. He grew up bow-legged and enchanting, with a larrikin grin that would light up a room. Even strangers in the street paused to share in his good nature.

When Will was two, his sister Elaine came along, and the pair were soon partners in mischief. Usually called Lainey, Will’s sister had long, fair hair that started the day neatly brushed, but ended it hanging in dank, sweaty hanks. Her knees were, like Will’s, permanently stained with dirt. By the time she was ten she could whittle a slingshot, skip a stone or ride a farm pony bareback just as well as he could.

At school, trouble was never far away. Their teacher was an elderly Methodist called Mr Humber, who had long ago lost passion for his vocation, and entertained himself with the singling out and humiliation of various members of the class.

Will didn’t mind arithmetic, geometry, or even geography, but English was not his strong point. Most of all he hated to read aloud, a skill that Mr Humber believed should be practiced each day.

When he first took up his position at the school, the teacher would start the reading off with the pupil directly in front of his desk, then work his way across, and down to the next row. Will responded by sitting at the back. When the teacher reversed this choice, Will moved to the front. After a while, the system became random, so Will sat somewhere in the middle and hoped that the morning recess would arrive before it was his turn.

Back on the farm Will Jones was afraid of nothing. He could stare down the old jersey bull, and grab a tiger snake by the tail, but one look at the thick spine of the Fourth Reading Book for Use in Schools made him break out in a cold sweat, and sent a tremor up his spine.

Sometimes he was lucky – a couple of big grey kangaroos might wander into the school yard and need to be hunted out. Now and then the teacher became so immersed in leading the class in reciting their times tables, over and over again, waving his hand like a conductor’s baton, that he quite forgot about reading at all.

At least once a week or so, Will’s turn came, and his guts turned to water.

© 2026 Greg Barron – Photo Courtesy of National Library – New chapter soon!

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this post!