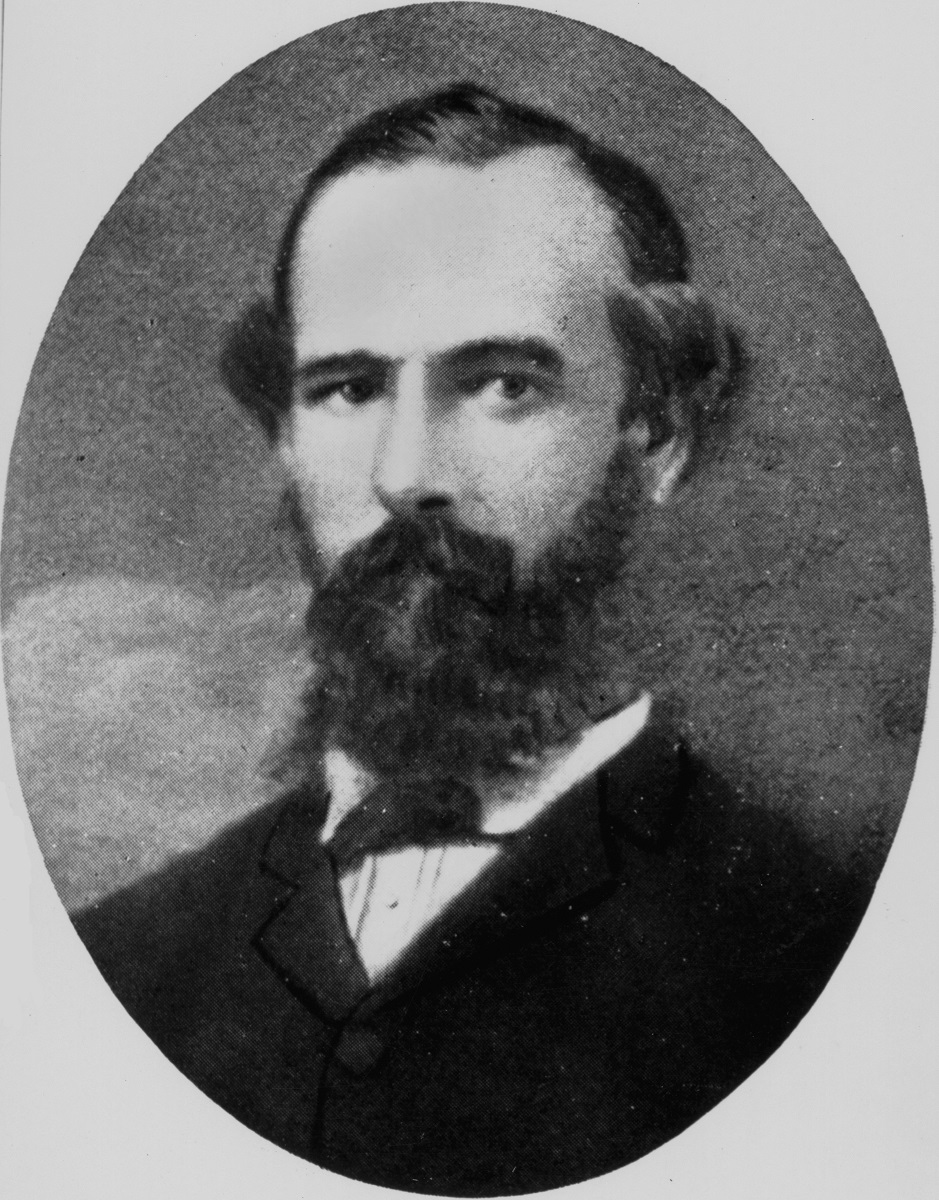

When Irishman, Lieutenant Charles Henry Buchanan and his wife, Annie, emigrated to Australia and took up a New England station called Rimbanda, they had no idea that their son Nathaniel would one day become known as the greatest drover the world has ever seen. Nat grew from a cheerful and adventurous lad into a competent man, with an even temper, incredible organisational skills and an unerring sense of direction. Nat ‘Bluey’ Buchanan was a bushman par excellence with a passion for new horizons. He single-handedly opened up more country than some of our most famous explorers.

In 1861, for example, Nat and his business partner Edward Cornish were out exploring in Western Queensland. Having taken up land to create Bowen Downs Station, they decided to poke around much further to the west. Penetrating all the way to the Diamantina River they discovered the tracks of a camel train. The tracks were, it turned out, made by one of the most expensive expeditions in the history of white exploration: Burke and Wills on their way from the Cooper Creek Depot to the Gulf of Carpentaria. That Buchanan and Cornish came upon those famous men and their entourage, while ‘poking around’ out west, with just one tracker and some packhorses, is a good illustration of the difference between independent bushmen and government-sponsored explorers.

A few years earlier, Nat’s working life had started out with the taking up of a station north of Guyra called Bald Blair, in partnership with his brothers Andrew and Frank. The trio also embarked on an unsuccessful trip to the Californian goldfields. When they returned, Bald Blair was laden with debt and had to be sold.

Nat polished up his droving skills, taking herds of sheep or cattle to the goldfields and interstate, following this profession for at least a decade before heading for Queensland and the vast frontier. His first real foray into Western Queensland was from Rockhampton with William Landsborough in 1860. Within a year they had formed Bowen Downs station on the Thomson River, and Nat was installed as manager.

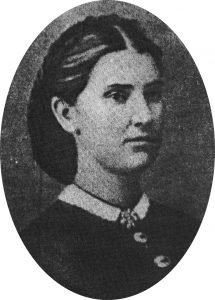

Nat met the attractive brunette Catherine Gordon when by chance he rode into her family’s campsite, on the Burnett River near Rockhampton. According to Bobbie Buchanan, Nat’s grand-daughter, Kate was ‘a natural horsewoman, and an accomplished rider. ’ She was also a stunning young woman, and Nat was captivated.

The young couple were married soon after, and Nat took his bride out to Bowen Downs in a buggy.

Married or not, Buchanan had no intention of living a settled life. After checking out much of Western Queensland he started exploring the Gulf country around Burketown, looking for suitable pastoral land for his business partners.

The strain of constant travel did tell on him, and Kate was by then pleading for some normality. In 1870 Nat and his brother Andrew took up a selection of land on Deep Creek, near Valla, NSW. This was still wild country then, frequented by cedar-getters and fugitives. The brothers and their families built bark and slab houses on the river bank, where they raised goats and chickens, planted a few acres of corn and cleared land for cattle. The plentiful fish in the creek varied the diet nicely.

Essential supplies were purchased via a fifty-mile ride to Kempsey, and mail was delivered into a letterbox nailed to a tree on Valla Beach, accessible by a long row downstream. Kate must have hoped that her man had grown roots, but Nat’s adventurous years were barely getting started.

Pining for open country, and sick of the humidity, Nat moved Kate and their sons Gordon and Wattie north again. He managed Craven Station for a while, then took on his first big droving contracts. He was the first European to cross the Barkly Tablelands in 1877, sparking an explosion of land speculation. Most lease contracts, moreover, stipulated that the run had be stocked within two years. The owners were crying out for cattle and men to drove them.

Now in his fifties, Nat led the largest cattle drive in history – 20 000 head from St George in Queensland to Glencoe in the Northern Territory. He made the record books again a few years later, delivering the first cattle to the East Kimberley. One of his most harrowing achievements was the blazing of the bleak Murranji Track, from near Daly Waters to Victoria River Downs.

Nat’s descendant and biographer, Bobbie Buchanan, described him as a ‘confident, strong-willed and uniquely self-sufficient man of great integrity. ’ His organisational skills were legendary, and his ability to keep tough men on track and working together no less impressive.

On a drive through the Gulf in 1878, Nat was forced to head back to Normanton for provisions. He was away for some weeks, and the man he left in charge, Charles Bridson, allowed some very insistent Aborigines who knew a few words of pidgin to talk their way into the camp. Bridson then rode off and left another man, Travers, alone in the camp.

Travers was making damper, dusted to the elbows in flour, when a steel hatchet that had been lying around the camp cleaved deep into the back of his skull. The event set off days of drama and revenge killings. Buchanan, on his return, was understandably incensed.

Nat’s next plan was to bring his family together on one of the largest cattle runs in history – Wave Hill Station – one of several leases Nat took up in partnership with his brother. Unfortunately the skills that made him a great drover and adventurer did not extend to management. Distance to markets and attacks on stock by the local Gurindji people were the two most important issues.

Nat, by the way, was known for a generally conciliatory approach to Aboriginal people, and was spoken of fondly by Indigenous workers in oral histories from the region. Cattle, fences and men were not welcomed by traditional owners – the Europeans were invaders after all – and conflict was a fact of the frontier. Buchanan, however, was never party to the ‘shoot on sight’ mentality of some frontiersmen.

In the 1920s Territory bushman, and chronicler Tom Cole came across an old Jingali man on Wave Hill Station, who the whites called Charcoal. Charcoal had worked on Wave Hill and in droving camps with Nat Buchanan as a boy and young man.

During an attack by wild blacks on the station, Charcoal used his rifle to shoot one attacker out of a tree. Bluey Buchanan, or Old Paraway, as his men called him, was furious, Charcoal had never seen him so angry. ‘You shot one of the poor bastards dead?’ Bluey roared. ‘Jesus Christ! You shouldn’t have done that!’

Even at the age of seventy Nat was out exploring again, searching for a stock route from the Barkly Tableland to Western Australia. His health was poor by then, and in 1899 he retired to a small property near Walcha, New South Wales, with his beloved and long-suffering Kate. He died two years later, and his gravestone stands in the Walcha cemetery, along with a plaque commemorating his life. Kate lived on until 1924, at which time she was buried beside her husband.

The most fitting epitaph for this great man is perhaps the words some of his contemporaries wrote about him. Charlie Gaunt wrote: ‘Buchanan had the gift of bushmanship and location. He was a fine, genial companion to have; you only had to look at Nat Buchanan to see in his physique, actions and general appearance a thorough typical bushman with the face showing dogged determination and strong will power; one who would stand by you until the bells of eternity rang. ’

Stockman Billy Linklater, in his memoir, Gather No Moss, wrote of Nat Buchanan: ‘His willpower was indomitable, yet he was mild-mannered and of a most kindly disposition. ’

Finally, in the words of singer/songwriter Ted Egan:

Nat Buchanan, old Bluey, old Paraway

What would you think if you came back today? It’s not as romantic as in your time, Old Nat, Not many drovers and we’re sad about that.

Fences and bitumen and road trains galore.

Oh they move cattle quicker, but one thing is sure Road trains go faster, but of drovers we sing

And everyone knows Nat Buchanan was King.

Written and Researched by Greg Barron, September 2020

This story is part of the revised story collection: Galloping Jones and Other True Stories from Australia’s History. Browse our books here.