Will Jones and the Territory Mail

Will, with Little Blue at his heel, walked past the three drunks, who were now sitting in the dust. The man with the scarred back stared as Will went by.

‘Hey you,’ he called, ‘don’t I know you from somewhere?’

Will gave the man a hard stare. He remembered the face, but did not recall where they had met. The voice was familiar. It carried a trace of an old accent. European perhaps? Maybe German?

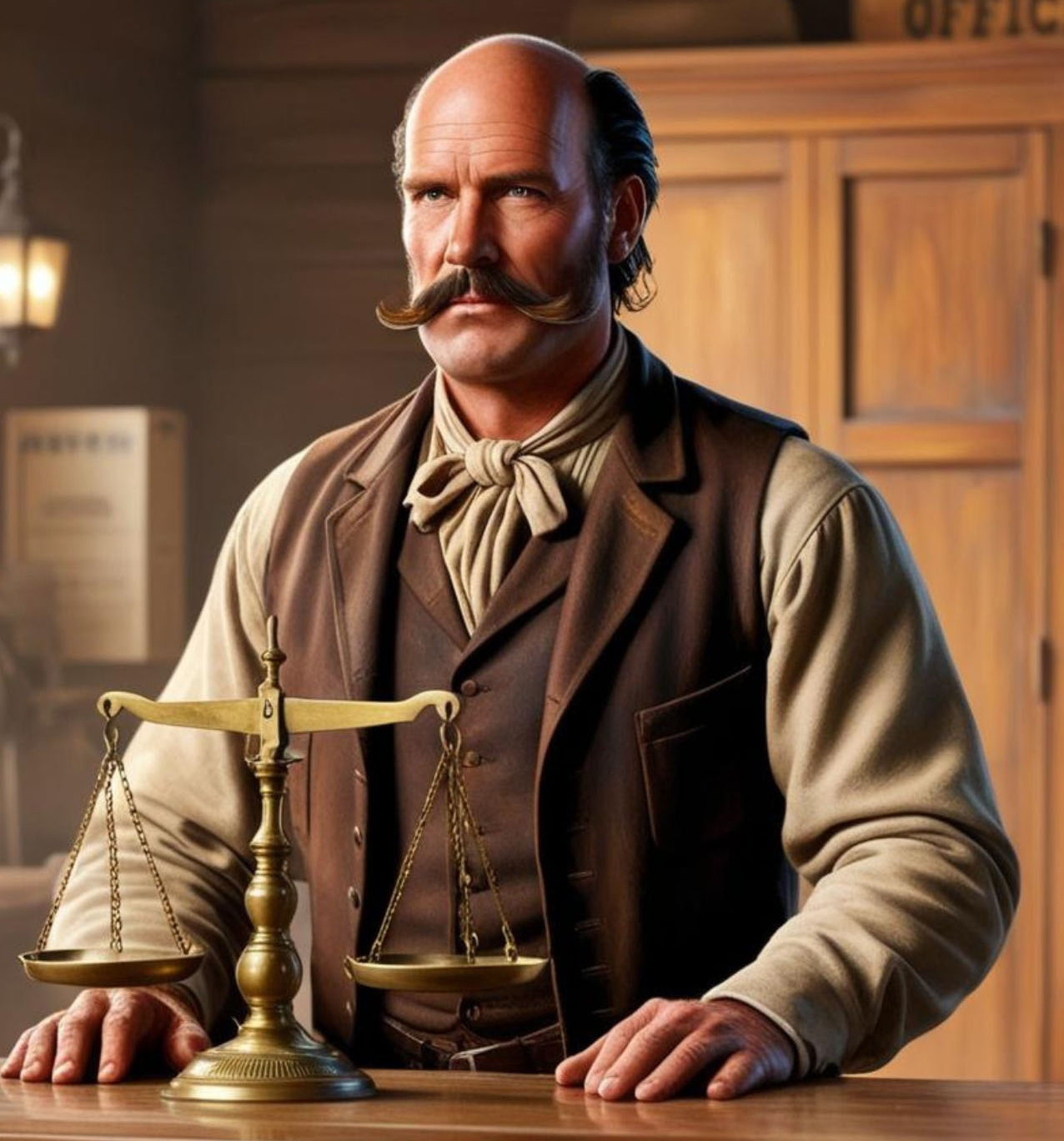

Saying nothing in reply, but disturbed at this development, Will walked on to the Post Office, where he lowered the rifle, so the barrel pointed at the ground, and pushed open the door. The postmaster was behind the counter, checking small packages on a balance scale. He was a well-built fellow, bald on the top of his head, but with dark hair, combed with Macassar oil, on the sides and back. He wore an impressive moustache, and was formally dressed, in defiance of the heat.

‘Good day,’ he said. ‘I wasn’t expecting any customers – our rowdy friends outside seem to have scared everyone indoors. Rather a bother, overall.’

‘Would you be Mr Kellick?’ asked Will.

‘That’s me. How can I help you?’

‘The feller at the pub reckoned you’ve got some work going.’

‘That would have been Kennedy himself – quite a scoundrel, did you know?’

‘Nah,’ said Will, ‘but it don’t surprise me much.’ In his experience, a dose of the scoundrel in a man’s makeup was necessary for survival.

‘Well, he’s right. I do require a man or two, but it’s not easy work, and I need the right applicant.’

‘Go on,’ Will encouraged him.

Kellick put an iron weight on the counter with a click, then gave Will his full attention. ‘Tom Maconsh of Buchanan Downs has the Territory mail run between here and the Macarthur River – Borroloola they’re calling it now. D’you know Tom?’

‘No mate,’ said Will. ‘We’ve come from over Clermont way.’

‘Well, he’s crook with malarial fever – by all accounts the Gulf settlements are rife with it. Right now Tom’s laid up in my spare room, with my missus feeding him soup and quinine.’ The postmaster narrowed his eyes. ‘A little too enthusiastically, in my opinion – Maconsh is a handsome devil. Anyway, the poor beggar is too sick to ride, but that mail has to get through, and I need someone to take it.’

‘How much is the job worth?’ Will asked.

‘Ten pounds to get the new bags through to the Macarthur – and all stations along the way. Ten to bring the Territory mail back here.’

‘That’s a long haul for twenty quid. What is it, four hundred miles each way?’

Kellick didn’t miss a beat. ‘About that, maybe a little more.’

Will considered this carefully. Eight hundred miles on a hard bush track and the wet season thrown in. Yet, twenty quid was enough to stake his little gang as far as Palmerston, if they chose to take that route.

‘I’ll do it,’ he said, at length.

Kellick stared at Will for a moment, then squinted. ‘It’s wild terrain – up by the Playford River, along Creswell Creek, and on to the Macarthur. Too big a job for one man who doesn’t know the country, no matter how good a bushman he is – specially with the Wet underway. Even worse, the Irishman and his mates out there are just a sample of the ruffians at large. There’s a gang of cattle and horse rustlers operating in the border country. If troopers from one colony get on their trail they just skip over the line. Then there’s the possibility of catching a spear in the chest. Don’t even think about taking this on unless you’re well-armed and willing to use your weapons to deadly effect.’

‘There’s four of us – and one of me mates worked on the goldfields around Pine Creek, so he’s been this way before.’ It was true, Fat Sam had been on the Top End goldfields before having a serious falling out with his countrymen. He’d been terrified of meeting up with his fellow Cantonese ever since. ‘All of us can shoot,’ Will added, ‘and aren’t no strangers to trouble.’

The postmaster walked to the window, looked down the street at a sharp angle and saw Jim, Sam and Lainey and their horses at the public trough. ‘This lot your mates?’

‘That’s them,’ said Will. A long silence followed, which seemed to indicate that Kellick was not impressed. Will sighed, not interested in begging, but keen to plead their case. ‘We need the work. It’s been a month since we managed more than a few days – now the Wet looks like setting in no one needs men – even the drovers are off the track now.’

Kellick smiled, ‘Well … you seem like a sturdy fellow, used to the outdoor life. The job’s yours, but you don’t get paid until you’re back here with the return mail. By then Tom should be on his feet and ready to take over again.’

‘Fair, I s’pose,’ said Will, ‘but I’ll need five quid up front fer supplies.’

The postmaster scratched at his beard for a moment, opened a drawer, removed five sovereigns, and counted them into Will’s hand, each one landing on his palm, with the heavy authority of gold.

‘That comes off the total. Can you leave tomorrow morning?’

‘No mate, we need to get some feed into our horses, an’ a couple of days rest …’ Will inclined his head at the window and the drinkers outside. ‘But the sooner we’re out of this town and on the track the better, so how ‘bout Friday?’

‘That’ll have to do. I’ll be out the front at sunrise, with the mailbags.’

Will started to leave, then turned again. ‘That Tom Maconsh feller. I’d like to talk to him, before we go. There’s bound to be things he can tell us about the route that might be worth knowing.’

Kellick paused for a moment. ‘Worth a try, if you can get any sense out of him. Maybe leave it ‘til tomorrow – then pop into the house. It’s just next door. Doctor Blamey has been coming in at about ten, so maybe after eleven. Here, shake on the deal and consider it a contract.’

After the handshake, Will walked out through the door and onto the street. As he headed towards the rest of the crew, who were standing around the public trough with the plant, he saw a man on a horse riding down the street towards him. This was unusual sight, partly because the horse was a fine thoroughbred stallion, of sixteen hands at least, and looked to be in peak condition. The man in the saddle had the bearing of a natural horseman. His skin was very dark, but he was not, Will realised, of local stock, but of African heritage. Altogether, he was an impressive-looking man, and that made him stand out all the more.

The rider, now almost adjacent to Kennedy’s Hotel, also piqued the interest of the drunk Irishman, who Will now knew as Sullivan. He staggered out from the shade of his tree, holding a bottle by the neck in one hand, and his revolver in the other. He stared stupidly for a moment, his lower lip pushing like a bulbous tube against the upper. Then he started laughing.

‘Look at this!’ he cried. ‘An ape on a horse. A foin lookin’ horse at that.’

The black man stopped his mount, then turned and stared at the Irishman, saying nothing aloud, but speaking volumes with his eyes. Back down the street, a loud and rhythmic hammering started up from the blacksmith’s shop.

The Irishman started making ape noises, scratching at his armpits and screeching. His two mates were laughing now too. The man with the scars near doubled over with mirth. It was a childish display, a ridiculous thing for grown men to do. Will felt a surge of annoyance, but he could not keep his eyes off the newcomer’s face, which was now blank – as if he had pulled down the shutters on his emotions.

That might have been the end of the encounter, but then, with scarcely any sign apart from a sharp dig of his spur-clad heels, the black man slowly and deliberately set his horse on a collision course with Sullivan and his mates. The stallion pushed off his back legs and into a gallop, straight at the three drunks. First the Irishman scrambled out of the way, then the others found their feet and sprang out of the path of the horse which was, to all appearances, about to trample them.

Drunk as he was, the Irishman tripped on a tree root, and fell sideways to the ground, dropping his revolver and the bottle, so the whisky spilled. His elbows and hip struck the ground hard, and there was a grunt as air left his chest.

As Will watched, a smile tugging at his lips, the rider stopped his horse so abruptly that it was as if his mount had hit a wall. Now it was his turn to laugh – a rich chuckle, full of manly strength and the enjoyment of life. Before the victims of his fiery charge could react, he turned his mount and rode off at a walk, heading towards an alley that led up behind Kennedy’s pub.

Will admired the man – for charging at three armed, drunk and unpredictable strangers, with no intention to hurt or main, with as much a sense of fun as anything. This kind of devil-may-care behaviour had always amused him.

The Irishman, realising that he had been humiliated, scrambled to his feet, gathering his wounded courage. ‘Hey ape, you’ll regret that caper.’ The black man did not turn, just led his horse around to the rear of the hotel building.

Will walked on past the tree, towards the trough where his mates were waiting, while Sullivan blathered on. His face had turned as red as a beet. His trousers were covered with dust and old piss-stains.

‘Hey you. Did you see what that dog did to me?’ Sullivan screeched at Will. ‘I’ll have him, you wait and see.’

Will had the feeling that whatever he said would cause offence to the drunken man, so he said nothing and walked on, keeping his grip tightly on his rifle so that he could respond quickly, if necessary.

As soon as Will came up to his mates, Lainey turned on him. ‘That Irishman is off his head – he’s scarin’ the tripe outta me. Let’s get out of here.’

Sam and Jim said nothing, but Will could see that their nerves were stretched.

‘Probably not a bad idea,’ said Will, ‘but how did you go at the store?’

‘No chance of credit in this town,’ said Lainey.

‘We don’t need it now,’ Will said, thrusting a hand in his pocket and jiggling the coins the postmaster had given him. ‘But let’s take the horses away from this lot – go and have a rum or two, then we’ll buy rations. Here, let’s lead the horses round the back of the pub where that feller just went, must be stabling there.’

‘If we’re gonna go, let’s shake a bloody leg,’ said Lainey. ‘This place makes me nervous, and I’d rather be on our way.’ She inclined her head at the storm clouds building up on the horizon. ‘Looks like it might bucket down again before long, too.’

As they crossed the road the three drunks stopped to watch them, wary enough of the rifles not to interfere. The Irishman had a strange expression on his face by then – something hard, bitter and callous that comes to some men when they have been drinking grog for many days. Something that Will had seen before.

‘I’ll have that dog,’ Sullivan shouted again. ‘You’ll see if I don’t.’

©2025 Greg Barron

Continued next Sunday

Read previous chapters here.

Get earlier books in the Will Jones series at ozbookstore.com