Work at the Doomadgee Mission continued, despite rain and humid heat. Through it all, Len Akehurst toiled from before dawn to long after dusk, assisting with building works, teaching lessons, carrying water, performing the occasional baptism and preaching at prayer meetings. He had, during his training, completed a course in basic dentistry, and ringers from nearby stations would sometimes ride in to get a tooth removed, or an abscess drained.

Meanwhile I found that if I applied myself to my thesis work for an hour or two each morning, my grasp on the local languages grew apace. I became quite fond of Dorothy, and I know that she understood my interest in the story of Joe Flick. We both felt in our souls the sadness that underpinned the tale. A friend from Brisbane sent her an old newspaper clipping about Joe from one of the city papers – sensationalist nonsense, it seemed to me – and this she presented to me, as an addendum to my notes on Kitty’s retelling.

Meanwhile, amidst the occasional berthing of the supply boat Noosa down in the river, the shenanigans and politics of the camp, and the never-failing delight I took in the chattering, friendly joyfulness of the mission children, my meetings with Kitty continued.

I learned to wait while she rolled tobacco between her palms, stuffed the bowl of her pipe full and lit it with an ember from the fire. Seeing how badly some parts of Joe’s story affected her, this ritual allowed her time to collect herself.

‘By and by I’ll tell you about that Constable Hasenkamp,’ she said to me. ‘That p’liceman who took Joey in.’

‘If you want to,’ I said.

Kitty took a deep draw on her pipe, watched the stream of smoke she exhaled critically, and began.

Mounted Constable Harry Hasenkamp was square-jawed, five feet ten in height, broad shouldered and handsome in his blue serge jacket, and as hard as granite. Like Joe Flick, he was the son of a German immigrant, his father Adolphus then being the pound-keeper down south in Ipswich.

Harry Hasenkamp was good mates with Jim Cashman. Their children played together when the publican was in Burketown, and they drank beer shoulder to shoulder at Missus Synott’s Commercial Hotel. Both men were shocked that Joe would have had the gall to shoot at a white businessman, no matter what the reason.

Now, riding with two trackers up the Gregory on their way to Henry Flick’s claim, with the purpose of arresting Joe, Hasenkamp took no chances. He prided himself on never shirking from his duty, but nor did he take unnecessary risks. With his wife, Mary Jane, four daughters and a son back in Burketown, he had no desire to be carried home in a wagon tray.

When the lead tracker spotted Joe heading towards them, along that narrow river track, Hasenkamp ordered his men to dismount, take cover in the scrub, and train their Martini-Henry carbines on the lone figure as he walked his horse towards them.

‘Stop there, Joe Flick,’ called Hasenkamp as soon as Joe was within earshot. ‘Dismount and kneel.’

Joe had seen men shot for running, so he did as he was told, getting down on one knee with his arms in the air, still holding the reins in his right hand. The police surrounded him, forefingers resting on their triggers. One took the reins, another lifted him by the shoulders and patted him down, taking his knife and a couple of cartridges for the revolver he no longer carried, rattling around in the pockets of his dungarees.

‘Where are you off to, Joe?’ asked Hasenkamp.

‘I’m riding in to give myself up.’

‘Smart boy, at least that saves us the trouble of looking for you.’

‘Did I kill Mrs Cashman?’

‘No, you did not. Though you tried hard enough to kill her husband. You shot nothing but a wall, yet if your aim was better you’d be swinging from a rope inside a week. As it is you’ll spend a good deal of your youth learning better manners.’

Joe said nothing. He instinctively understood something about men in authority. That they were friendly as long as he was a good and respectful ‘boy,’ and played the part they expected him to play. Now that he had turned on one of them, the reaction was swift.

Hasenkamp secured Joe with a neck-chain, fastening it with a Yale lock. The cold iron sat hard against his young skin, but the humiliation sat harder still. This treatment didn’t seem fair. After all, apart from the man who raped his mother, and was rightly deserving of a beating, Joe had hurt no one.

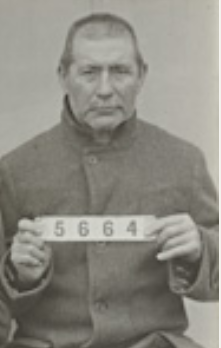

The following day, at Burketown Police Station, after a sleepless night camped in irons, and many hard miles on horseback, Joe was formally charged. Hasenkamp wrote words on a page that made him legally responsible for the ‘Attempted Murder of Patrick James Cashman.’

Joe could not read, but saw the ink-lines that made up those words winding like snake-trails across the charge-sheet and they chilled him to the bone.

The lock-up was a fortified hut just behind the station, and Joe was too miserable to do anything but sit on the wooden bench inside. He was the only occupant, with the sounds of drunken laughter from the pubs, the occasional cries of curlew and owls, and chattering geckoes for company.

The next morning Constable Hasenkamp, with freshly-shined Napoleon boots and pressed cord breeches, walked Joe to the court house, gripping his arm like a big-game hunter with his kill, for the benefit of the crowd of local business types and loafers who gathered to see Joe face court.

Inside, the magistrate occupied the bench in self-important silence, in his dark suit and bow tie. His name was Alick Clarence Lawson, just thirty years of age. His wife Olympia sat in the third row, looking admiringly up at her husband, while the buttons of her bodice strained against her generous proportions.

Alick and Olympia had been married the previous December, in the midst of an Albert River flood, and the wedding party were forced to trudge through a foot of mud and water to attend the ceremony. Reports of the best man, diminutive Lawn Hill Station owner Frank Hann, lifting the eighteen-stone Olympia down from her palanquin outside the National Bank were now local legend.

Yet, in spite of the local fun-poking at his wife and nuptials, Police Magistrate Lawson was a young man who took himself and his job very seriously. He peered down at Joe from a seeming lofty height, his bowler hat sitting beside him on the bench.

In near silence Lawson considered the evidence as it was presented: written testaments from witnesses, a scrap of weatherboard complete with embedded slug, formerly a panel from the Beames Brook Hotel, and a matching revolver cartridge from Joe’s pockets

Jim Cashman swept in, wearing a morning coat, knee-high riding boots and carrying a safari hat in one hand. He shook hands with Harry Hasenkamp, swore on the Bible to tell the truth and nothing but the truth so help him God and stepped solidly up to the stand, affecting the air of a man torn from the important work of his day.

Glossing over the incident with his ‘employee’ and Joe Flick’s mother, Cashman spun a tale of Joe riding up to the pub, armed and raving, taking deliberate aim and ‘missing’ due only to the Grace of the Almighty. No one there doubted that Cashman was an eloquent and capable witness.

When Joe was asked to present his side of the story his mouth clamped up, and he could not speak, cowed into silence by confusion, fear, and this terrible turn his life had taken. Various members of the court, including Hasenkamp, the clerk, and then the Magistrate himself attempted to cajole and gentle Joe into speaking, but he remained silent, shoulders hunched, and shaking visibly.

‘Struck dumb by guilt,’ called a heckler from the audience.

In blessed relief, they let Joe sit again, while Police Magistrate Lawson scribbled notes and re-read statements. Finally, he looked up, ‘Will the prisoner now stand.’

Joe came to his feet, shaking in every muscle and limb, cowed by this first experience of English justice. He saw no pity on Alick Lawson’s face, just self-belief in his role in delivering the law, a cog in the wheels of justice that stretched all the way to Queen Victoria herself.

‘Joe Flick,’ Lawson said. ‘I have examined the evidence, and find that there is sufficient cause to believe that you did, most feloniously, attempt to murder Mister Patrick James Cashman. I commit you for trial on the twenty-second day of March 1888, at the Supreme Court, Normanton. Bail is refused.’

There was a smattering of applause from the audience, and a muted but heartfelt wail of anguish from one woman, right at the back of the room, for Kitty herself, with Henry beside her, had come to see her son face court.

From his place near the front of the court, Harry Hasenkamp smiled.

And while the rain pattered down on the canvas tarpaulin I’d roped to four trees at Kitty’s camp, to improve her living conditions somewhat, and so we could talk without getting wet, I marvelled at how fast lives can change. At how one thoughtless act can send a soul hurtling down the wrong path.

‘We went along there that day in the Burketown courthouse, you know,’ Kitty told me. ‘Me an’ Henry up the back. By an’ by they bring Joey along outside. He couldn’t look at my eyes, poor boy. What a thing for a woman to see the babe she suckled, there in chains, and all because he fought for her, because he loved his Mama and fought for her.’

‘It broke your heart?’ I said.

‘Yeah, my heart broke,’ Kitty agreed. Her eyes became as weathered and old as the country she walked on. I saw something inside – a relic of the cycles of life, of mother and child, all down through the generations.

Kitty took up her pipe, and would not speak another word to me that day.

© 2019 Greg Barron