In these next few history posts I’m going to share some of Charlie Gaunt’s family background. These stories don’t appear in the novel, Whistler’s Bones. They’re extra background, and should be interesting whether you intend to read the book or not.

Long before Charlie Gaunt rode the plains of Western Queensland and the Gulf Track across to the Kimberleys with the Duracks, his mother was a passenger on an immigrant ship, plying the seas from England to a new life in Australia.

The family sailed on the Royal Mail Steamship Africa, in late 1852, and for five months nine-year-old Augusta Marion Fuller made her family’s thinly partitioned space on the steerage deck her home. 450 immigrants were sandwiched into this converted cargo hold at the stern, with enough head space only for children to stand. The sun barely penetrated, and the air stank of close-packed, unwashed humanity.

Hundreds of people used two overflowing privies with queues all day and night, talking or arguing in Scottish, Irish, Welsh, and every dialect of England. All were desperate poor. The dangers and possibilities ahead were the main topics of conversation.

Augusta’s father, Adam Fuller, was a sick man. He needed a warm place to live. He was also a bankrupt. Augusta didn’t really know what it meant except that it had happened to him twice and that they had no money. She understood that Australia was their last chance for happiness.

All the time, day in, day out, the side-paddle churned and the Africa faced the big green ocean swells. Augusta sang nursery rhymes to the rhythms of the steam engines.

Augusta’s mother, Anna Maria, held the tiny hands of her daughters. ‘The Mate told me that we’ll reach Melbourne in just one more day,’ she said. ‘Your uncle George will be there to meet us. He’ll help us. Da will get well then. God won’t let him die.’

From then on they counted the hours and the miles, while Adam held on, falling lower and lower. He was still breathing, however, when the ship passed through Port Phillip heads and the Africa came alongside the Town Pier in Hobson’s Bay.

Augusta looked out from the rail, to another long pier that jutted into the bay to the north. There were building frames visible behind the beach near the Customs House. Further on was the vast slum of Canvas Town, a city of tents, the home of thousands of hopefuls on their way to and from the Goldfields.

Augusta had never seen her Uncle George but she scanned the crowd as they waited out on the concourse with their bags. Slowly the arrivals wandered off to their relatives or prepared to cross the sandy track to the settlement of Melbourne on the Yarra, on foot or by one of the many horse drawn vehicles for hire.

The unloading of the ships’ cargo started. Corpses were carried out first. One in twenty of those who had set out from Liverpool had already been buried at sea along the way.

Augusta and her family were spared the tragedy of death by only one day. The following afternoon, Adam Fuller died, and they had no choice but to move into the Houseless Immigrants home.

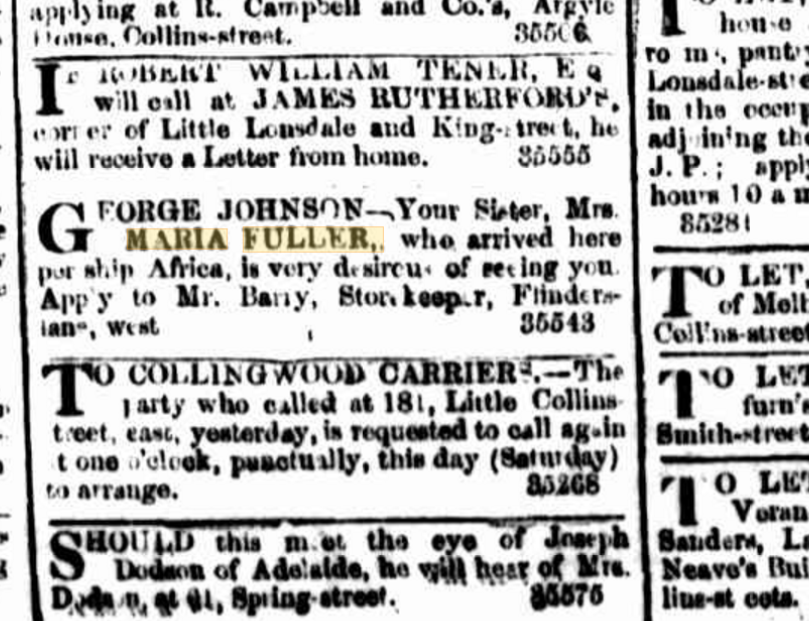

Anna Maria sent a desperate message to her brother George, who was supposed to have met them when they arrived. The following advertisement appeared in the Melbourne Argus on Saturday April 23, 1853.

GEORGE JOHNSON – Your sister MRS MARIA FULLER is very desirous of seeing you. Apply to Mr Barry, Storekeeper Flinders Lane, West.

That night when the destitute little family returned to their room, a big, sunburned man in his mid-twenties was waiting for them. Augusta watched as her mother ran into his arms. He was rugged looking and a little scary.

The man finally left Anna’s embrace, and looked down at the girls.

‘Hullo,’ he said. ‘I’m your Uncle George.’

He smelled of whisky. Augusta hid behind Amelia’s legs.

George was living in Ballarat, where the gold boom was in full cry. Augusta’s mother Anna was nothing if not resilient, and after a few years of living on the charity of her brother, she fell in love again. Henry William Cooper was the son of a coach builder from Dublin and owner of the Burrumbeet Hotel, on the shores of Lake Burrumbeet, near Ballarat.

Anna lied about her age to the celebrant, and most likely to her new husband as well. She was forty three years old by then, but the marriage certificate lists her age as just thirty-five. Partly, perhaps, for the vanity of her husband, who was thirty-seven at the time.

Augusta was twelve years old by then, almost certainly a flower girl. The ceremony took place on the north shore of Lake Burrumbeet, perhaps on one of those perfect spring days that Ballarat can produce when it feels like showing off.

George was there to give Anna away, and no doubt he did his best to drink the hotel dry at the reception afterwards. (The newspapers of the day were sprinkled with George’s minor run-ins with the law, mainly for drunk and disorderly behaviour and the odd fight.)

The wedding was a triumph, certainly much better than Anna’s taste in men deserved.

Within twelve months, however, Henry William Cooper was insolvent, and the Burrumbeet Hotel was sold for less than half of what he paid for it. In fact, a meeting of creditors was informed that Henry had paid three times the true value of the hotel in the first place.

Augusta and her sisters were again forced onto the charity of their family.

Continued next week.

The story of Charlie Gaunt is documented in the book, Whistler’s Bones by Greg Barron. The book is available from good bookstores and direct from the publisher at ozbookstore.com

Buy the ebook version here.