“It’s twenty years ago now since we settled on the Creek. Twenty years! I remember well the day we came from Stanthorpe, on Jerome’s dray – eight of us, and all the things – beds, tubs, a bucket, the two cedar chairs with the pine bottoms and backs that Dad put in them, some pint-pots and old Crib. It was a scorching hot day, too – talk about thirst! At every creek we came to we drank till it stopped running.”

So begins the first-ever published story by Arthur Davis, better known as Steele Rudd.

Born in 1868, Arthur Davis was six years old when he and his brothers and sisters, walking beside a cart piled high with furniture and farm equipment, arrived at “Shingle Hut” on the Darling Downs, there to make their fortune. “Dad” had arrived a few weeks earlier and knocked up a rough slab hut. Before long, through drought, flood and very occasional plenty the family had swelled to thirteen children.

The young Arthur, was, according to a much later recollection by his son Eric; “six feet tall—active and athletic—his carriage was erect—also his seat on horseback. He had a ruddy complexion with twinkling brown eyes—keenly alert and observant, with wrinkles at his temples which lent a humorous outlook. Kindness was one of his virtues, and he was generous to the extreme.”

At the local school, Emu Creek, Arthur was quiet and hard working. There was one little girl who liked to sit with him in the playground, and talk about horses, dogs and books. Her name was Christina Brodie, always called “Tean” for short.

By the age of twelve Arthur had finished school and was earning a living ‘picking up’ at the woolshed on nearby Pilton Station, and honing his skills as a jockey at the local picnic races. After a stint as a drover “out west” his mother arranged for him to apply for the civil service. His application was successful and he soon found himself in the foreign world of turn-of-the-century Brisbane.

His first job was with the office of the Curator of Intestate Estates, and a later book called “The Miserable Clerk” gives a clue to what he thought of this particular job. A flatmate, however, got him into reading Charles Dickens, and his interest in rowing led to him writing a series of articles under the pen name “Steele Rudder,” later changed to “Steele Rudd.”

After a few years in the city he missed the bush life so much that he began to read everything he could about the outback. Eventually, he had a go at writing his own stories. His first sketch of life growing up in his boisterous family, “Starting the Selection,” was published in the Bulletin Magazine in 1895, championed by J.F. Archibald, the force behind so much great Australian literature.

That same year, Arthur headed back home and asked his childhood sweetheart, Christina, to marry him. She was full of fun and good sense, and had a keen editing pen. It was “Tean” who first read and helped hone Arthur’s early stories.

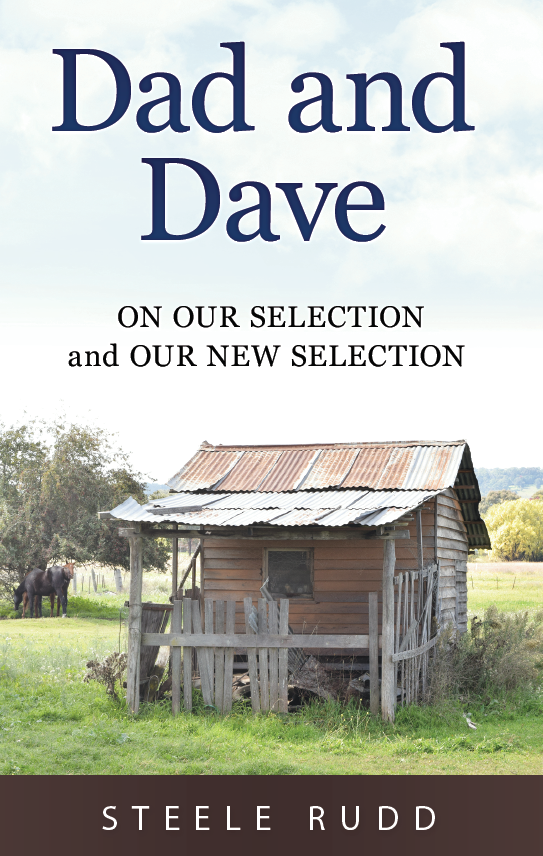

“On Our Selection” was published in full by the Bulletin Magazine in 1899, followed by “Our New Selection” in 1903. Both won popular and critical acclaim. Two of the main characters, Dad and Dave, became part of Australian folklore.

Partly because his bosses were jealous of his success, Arthur was retrenched from his public service job, and responded by moving to Sydney and starting his own magazine. Nothing could keep him down. As his son Eric later said of him: “He was always a man’s man, tough, testy, a good friend.”

All was not well with Tean. The lack of a steady family income tested her disposition. The magazine slowly dropped in sales, then was forced to close, making her state of mind worse. Believing that a big change might help, Arthur took the family back home to the Darling Downs, settling on a property called “The Firs,” where he bred polo ponies and entered local politics, becoming head of the Cambooya Shire Council.

During World War One their son Gower was badly injured at the Somme, and Tean’s “frailty” became full blown mental illness. The family were forced to sell up and move to Brisbane where she could receive special care. She was hospitalised permanently in 1919, remaining there until her death more than twenty years later.

“Steele Rudd” never stopped writing until his death in 1935, but made little money in his later years. A grateful nation endowed him with a “literary pension” to the tune of twenty-five shillings per week, for which he was apparently grateful.

Arthur published many other books and stories over his lifetime, including his ill-fated magazine, and but nothing ever approached the freshness and honesty of his first two works, On our Selection, and Our new Selection. They are true classics, and an insight into how life was, “back then.”

Written and Researched by Greg Barron.

Click here to view the sources for this story.

You can get this beautiful new edition including On our Selection and Our new Selection by Steele Rudd here: http://ozbookstore.com

This is an excerpt from Galloping Jones and other True Stories from Australia’s History by Greg Barron. Available at ozbookstore.com